Jump the Broom and Break the Glass (Sojourn America)

Faith. A word instantly comforting to some and off-putting to others, because it can be deeply intertwined with our upbringings. Some of us enjoyed the faith traditions we experienced growing up, others ran away from them. And still others of us are seeking a reconciliation of sorts, not just with a higher power, but really with one another, through our various faith traditions.

To understand how I experience faith and spirituality is to understand a few things about me: 1) my upbringing in the Christian faith tradition, 2) my marriage to a Jewish woman, 3) my exploration of the intertwinings of faith and religion, with culture, race and ethnicity, and 4) my journey to understand how our identities are informed by all of these things, and sometimes experienced in contradictory ways.

A Foundation of Faith

While the stories of three interrelated faith traditions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – start with a common father figure, Abraham, the story of my faith tradition starts with a mother, my mother: the late Rev. Gwendolin Sims Warren.

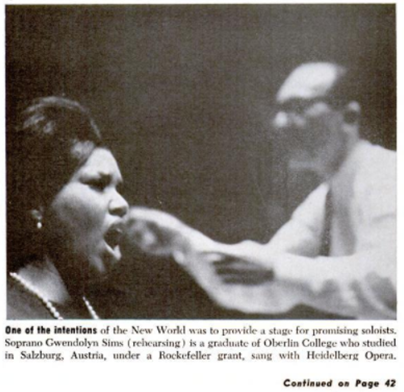

I come from a long line of ministers, my mother being the most recent one. She grew up in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, the oldest predominantly Black church in America. My mother was an only child, the daughter of an AME pastor, and niece and cousin to probably a couple dozen ministers in the Church. She was also a gifted singer and musician. She made her professional debut in the church at age 4. She grew up in the church, and eventually left to pursue a career as an opera singer, throughout Europe.

At the time, Black opera singers weren’t very appreciated in the States, but in Europe, talent was the thing and she had a lot of it, and so she found a home for her gifts.

Gwendolin Sims Warren, the opera singer. Image credit: Ebony Magazine.

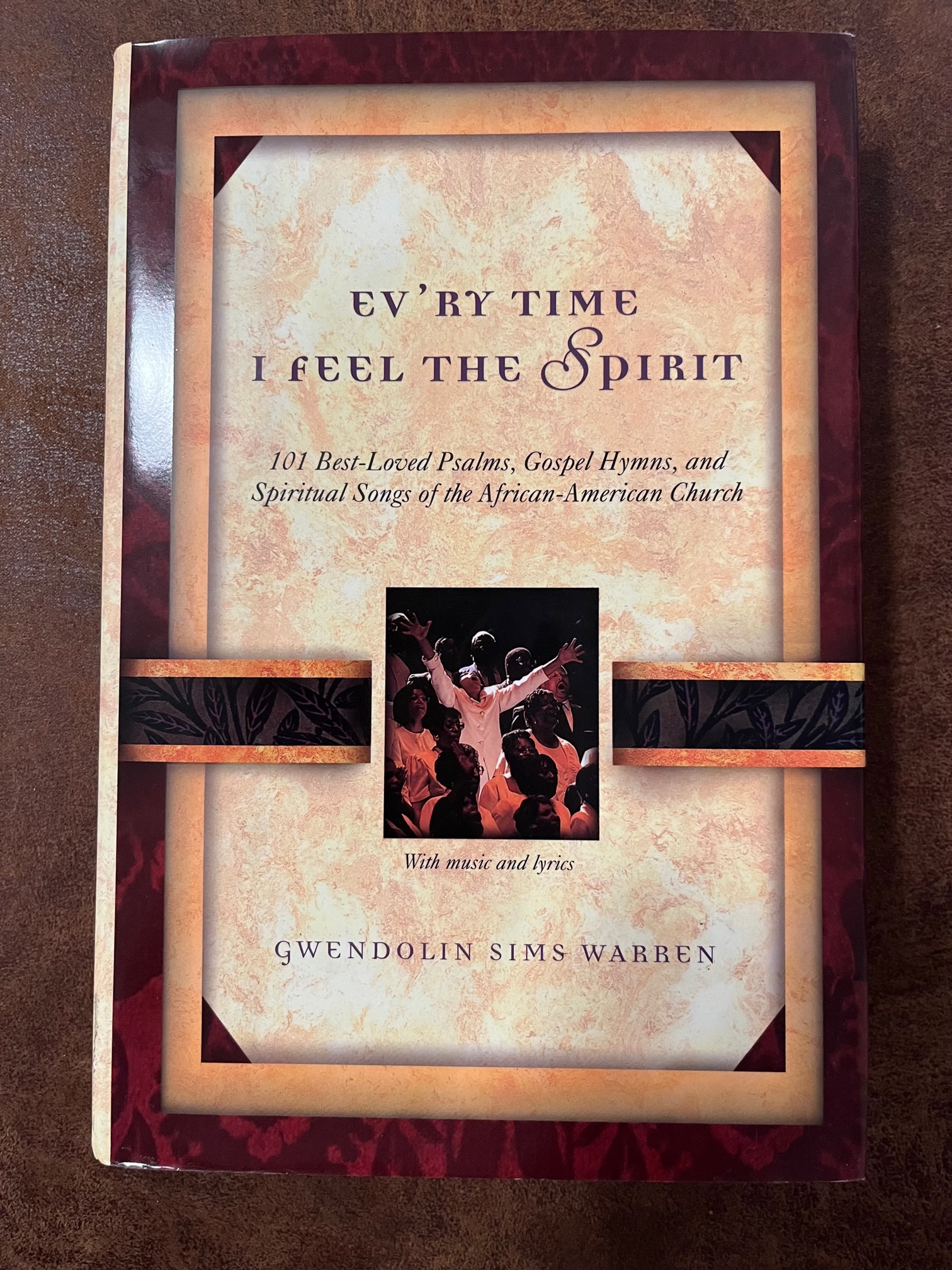

Eventually, she returned to the States, married and took up teaching and raising a family. In her mid-40s, she returned to what she saw as her original calling: the ministry. She pastored and served as minister of music in several churches, both non-denominational and AME, first in Tulsa, OK and then throughout New York City until she retired and moved to Richmond. I997, she wrote “Ev’ry Time I Feel The Spirit,” a collection of 101 psalms, hymns and spiritual songs that played an important role in the Black faith experience in America.

My mother’s book, Ev’ry Time I Feel The Spirit

I have a lot of stories growing up as a preacher’s kid. And this was conflicting for me ever since I was a teenager. At one point I thought I would follow in her pastoral footsteps, but on a deeper level, I knew that was not my calling. I also struggled with the way I saw faith and spirituality being expressed and experienced through religion, where sometimes the worst parts of our humanity – bigotry, hatred and hypocrisy – found fertile ground. This conflict, and my inability to resolve it by myself, contributed to me running as far away from the Church as I possibly could for a very long time; angry at how people twisted religion to suit their aims the world over, confused about the role of faith and spirituality in my own life.

There were two things, however, I was very clear about: 1) God – my Higher Power, the Universe, the entity, being and force beyond human comprehension – was bigger than religion. 2) I was quite angry with this being who was beyond my control, and who alternated in my mind between having zero interest in the self-destructive ongoings of humanity, and playing puppeteer as it pulled our strings and made us dance at whim.

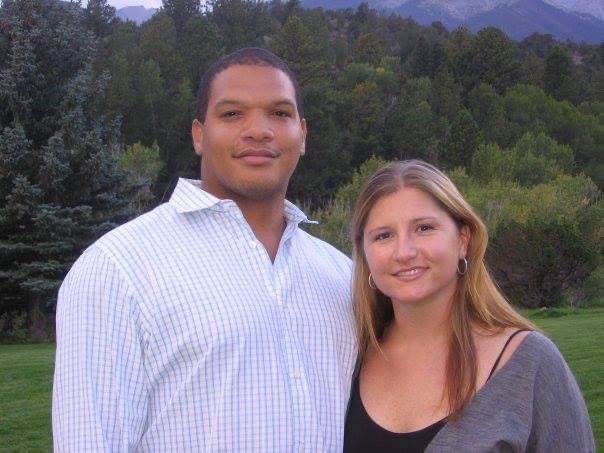

I experienced these conflicting emotions through much of my teenage years and young adulthood, acting out quite a bit along the way. And it was during this time – a few months after I turned 30 to be more precise – during which I met my wife, Darcy.

Darcy and Me

I’ll tell you up front, in addition to believing that God is bigger than religion, I’ve always believed two other things about life, even if I didn’t always understand them. I’ve always believed that my identity is PART of who I am, but it is not ALL of who I am. And I’ve always believed that love at first sight is possible – or at least that the incredible you feel it in your bones and you know it in your soul because you prayed for this person and look, there they are! kind of feeling was possible. 🙂

All three of those things were proven true when I met Darcy.

We met at a wedding in New York City in October 2002. I was the best man to my non-Jewish best friend who was marrying a Jewish woman, her first cousin, and we first saw each other the night before the rehearsal dinner, when all of her cousins were meeting up, which was their tradition. She walked into the bar where all of the family cousins were gathering. I saw her, she saw me, and we felt an immediate connection, the so-called electric charge. She walked up to the bar and I watched her all the way. After she ordered her drink, she turned over her shoulder and looked right back at me, and smiled. And yep, that was all she wrote. I knew immediately there was something between us.

And other people noticed it, too, because her cousins, who already knew me socially from our days hanging out in the City, immediately said things like, “Um, no, James.” But I knew then, as she knew, that we had connected. Deeply.

See? Love at first sight.

Two nights later at the wedding, I’m in a yarmulke, the only Black guy in the joint, and I guess interfaith love was in the air, because my date – a friend I brought to the wedding who was NOT Darcy, noticed how I kept looking over her shoulder at Darcy, and said, graciously, I think she wants to dance with you. You should go dance with her. And I’m going to go home. (And yes, we’re all still friends to this day.) So Darcy and I danced. And the rest was history.

And you know what? God was never a question or a problem for us. Humans, on the other hand? Well, that’s another story.

We struggled a lot in our relationship, almost right out of the gate, because of our humanity. Because of drama with our parents. Because of socio-economic differences. Because I had already been married. Because I had two wonderful sons. Because I was 30 and she was 24. Because she was Jewish and I was Christian. And I was Black and she was White.

We’ve always been up for a challenge, Darcy and me.

We started talking days after she returned home to Arizona, and started dating a few weeks later, eventually beginning a long distance relationship. Initially, we had thoughts of her moving to New York, which made a lot of sense, because at the time she had plenty of family in NYC (ironically, all of the cousins who lived in the City then now live out West), and of course, my whole life was in the NY/NJ area, where my kids and their mother, my mother, and my sister all lived.

And then my company decided to relocate to Richmond, Virginia. I had a really good thing going career-wise, and I really needed a break from the City. It was crushing me in so many ways, self-inflicted and not. So I asked her about moving to Richmond instead of the City. This was a big risk for her, and a big escalation for us. Our relationship was already both profoundly magical and deeply flawed. But we knew we couldn’t make it work from a distance much longer. We needed to be in the same place to make it work, because sometimes, as humans, we need the connection that only being in the same space physically can provide.

And so we wound up in Richmond, a place that represents at once so much pain and so much potential, so much division and so much community. We started to explore early on what the implications and opportunities were of us being together – race, faith, age, kids… it was a lot to work through, we weren’t always well-equipped to do so and we made it harder on ourselves than we had to. Still, even then, we had a sense of higher purpose behind our relationship, even if it didn’t look or feel like that every day.

Darcy and me, waaayyy back in the day. #Freshfaced.

We argued, we broke up, we reconciled. We talked about the future a lot. We talked about what it would mean to exemplify a relationship in which God rightly surpassed our religious definitions of Christianity and Judaism, to be the God of us all. We really wondered if the promise of the Abrahamic faith was a promise of unity, and if there was any hope – any hope at all – that it could be revealed through a shared belief in a common spiritual destiny.

These thoughts were almost too much, placing the weight of aspiration on a sometimes fragile relationship. There were so many times when it would have been easier to just go our separate ways. This is true not just of romantic relationships, but relationships in general, especially when faced with conflict. It can be easy to walk away, and sometimes that is the right thing to do, when the conflict becomes unhealthy. Other times, it’s easy to stay without addressing things because of fear. Sometimes, the hard thing is the right thing, and that is both to stay connected AND to work through the conflict with honesty and courage.

That is what we chose to do, and have chosen to do over and over again. Our love and faith in one another and in God helped us get through the difficult times, especially in the earlier years of our relationship.

Like when we got married.

When we decided to get married, we decided sort of spur of the moment (not our finest romantic moment). We were sitting in the living room of my house in Church Hill, and we were trying to make some decisions for the future. And while we always believed we’d be together, the time to make that decision was here. I still don’t quite know why it went this way, but we sort of looked at each other. I think I said, “We should get married.” I think she replied that she agreed, but her face said, is he really asking me to get married? So then I think I said, “Yes, we should get married.” And she smiled and sort of giggled and said, something like… “Okay…?” And then we looked at each other, laughed and said, “Did we just do that?” She wanted to make sure I was serious, and I was, absolutely. So the next question of course was when. And we decided we wanted to get married sooner rather than later. Like December. That year. Three months later.

I guess you could say we had a sense of urgency. And no, it wasn’t that kind of urgency. We were just like, if we’re gonna do this, let’s do this.

Planning our wedding, however, was tough.

We wanted a wedding that would bring together our families, our faiths and our traditions, but it was REALLY hard to find a minister AND a rabbi who would do an interfaith ceremony; most required “conversion” from the “other” party to the same faith, a few agreed they would perform a ceremony that included someone not of their faith, but practically no one said they would do a joint ceremony.

This was non-negotiable for us. There had to be true unity for our union: a true melding of our cultures and our communities, spiritually and ethnically.

Growing up, I experienced a lot of different church settings – all Black churches, all White churches where we were the only ones, and racially mixed churches. I experienced very traditional, Charismatic Christian churches, conservative churches, progressive churches. And everything in between.

I found it hard to find a church where I could feel at home, and where all of my family could feel at home, with all of our identities, without someone trying to change who we were. So I wasn’t active in any church at this time, because I wasn’t comfortable in most of the places I had found.

There was, however, a special place that always spoke to me. It was Richmond HIll. Knowing they were an ecumenical Christian fellowship gave me comfort, that I could navigate the spiritual part of the journey without the denominational conflicts.

We found a minister there, Rev. Harris. We asked her how she felt about an interfaith wedding. She shared her perspectives openly and honestly. She said, I’m willing to explore it with you. She had never worked with a rabbi, so she didn’t have any recommendations. So Darcy started researching rabbis who would perform an interfaith wedding. And just like it was for me, they, too, were hard to find. Eventually though, we found a rabbi from Maryland, Rabbi Braude, who would do an interfaith ceremony – not just a Jewish wedding with a non-Jewish participant.

Again, this was totally new for both the minister and the rabbi. Darcy and I eventually had to script what we desired as an interfaith ceremony, relying on our parents for help with the traditions of faith and culture, just to give our minister and rabbi something to actually react to.

And to our joy, they said yes. They agreed to co-officiate.

And so we wrote our wedding ceremony out, it was truly a co-labor of love. These two faith leaders and our families helped us fuse everything together. Looking back on that day, there was a lot of courage being demonstrated, because almost no one in the room had ever been part of something like this.

My mother sang hymns, dear to the Black faith tradition that we used to sing in church, with a string quartet. And my father-in-law did the things fathers do in the Jewish tradition and in Judaism. Our families stood up for us, and we got married under a chuppah.

And we had both the minister and the rabbi co-officiate and preside over the ceremony, taking turns leading various parts according to the respective faith traditions. We were surrounded by family and friends, who told us they had never experienced such a love-filled and spiritual wedding as this one.

Our wedding in December 2006.

Now in the Jewish tradition, after you get married, you “break the glass.” A glass is typically wrapped in cloth and placed in a way for the groom – or both – to step on, and crush the glass. There are a number of interpretations of this tradition, and here are two: one, the breaking of the glass serves as a reminder of the destruction of the first temple; and two, it also symbolizes the couple’s breaking with their past lives so they can create a new family together.

These are the glass shards from our wedding.

The glass shards are kept and used to create a gift, such as a mezuzah for the doorframe, or candlesticks. This further symbolizes the idea that the Temple will one day be rebuilt, closing a loop between God and humankind, and we go from mourning to celebration. Likewise, this gift memorializes the new family that has been created together.

And in the Black tradition, after you get married, many couples “jump the broom.” This tradition has a long history that includes different cultures and continents, including in Europe in the 18th Century, as a practice among those who would have been on the margins of the British empire, such as the Welsh, or the Irish.

This is the broom from our wedding.

To that point, it has almost always been a practice of people who were excluded or oppressed by the broader nation they found themselves in. This was especially true for enslaved Africans in the American South because they had no legal right to marry before the Civil War.

When practiced in Black culture today, it is a way to honor the ancestors.

So as soon as we were pronounced husband and wife, you know what we did. We jumped the broom and we broke the glass!

And In doing so, we combined two of the more memorable aspects of our families’ respective marriage traditions. We have the broom in our home today, and we are keeping the glass to put in a menorah. We have a mezuzah for our door frame that Darcy’s mother gave us when we moved into our new home, which serves as a reminder of the relationship between us, and our relationship with God.

The mezuzah on our doorframe.

In the years since, we’ve been through a lot as a family. A WHOLE lot. But we’ve made it through by staying connected through conflict.

Again, it would’ve been easier if Darcy had just married a nice young Jewish man in Tucson, AZ like her parents might have wanted her to (at least before they met me, lol… or maybe, even after 🤣).

It would’ve been easier if I remarried a churchgoing Black woman. (In all honesty, if it were up to my mother, I never would’ve gotten divorced, but again, that’s another story for another day.)

There were times we questioned this. Had we made it too difficult on my sons? Had we made it challenging for our children to be? Had we abandoned our people? Had we turned our backs on our own kinds?

It would’ve been easier.

But it wouldn’t have been better.

We wouldn’t have seen what is possible, when we resist the cling of our respective tribes to make new ones.

We wouldn’t have known what it feels like to find out that God is bigger than Shabbats and Sunday mornings.

We wouldn’t have known what it feels like to be united despite division.

We wouldn’t have been prepared for the world we are in now. For the world my adult sons are right now building their own lives in. For the world we’re raising our little biracial, interfaith babies in, who only know love. For this blended family who teaches me so much about love that I can barely give it words.

Our Family.

No, we wouldn’t have had any of this.

But now we do. And I think that our experience as a “little” us provided a bit of insight into what ails the “bigger” us.

Connecting Through Our Conflict

So let’s talk about us: you and me. We. America.

It appears as if something has happened to us, on the way to us.

We have allowed conflict to rule us, to reshape us, to DEFINE US.

In one sense, we’re born in conflict and yet we are so dependent on others. We come into this world, helpless, kicking and screaming, in a moment of sheer joy that is also often a moment of jeopardy for both mother and child.

Joy.

Jeopardy.

Birth.

Pain.

Truly, conflicted at birth.

The same is true for this country’s origin. In fact, this has been the story through so much of our human existence. This has been true for Black people in this country. This has been true for Jewish people in this country and in Europe. This has been true for the Indigenous people who were in this country before the Europeans.

And all of these communities know conflict.

On this continent, tribes warred with one another long before the first Europeans arrived on these shores.

The story of Europe, where so much of our American identity and customs (and perhaps, many of your ancestors) come from, is a story of devastation told as triumphs by conquerors.

The African continent holds untold stories of rich civilizations and deep conflicts that preceded colonization.

The Middle East, the Holy Land, an area so contested for millennia, is claimed as holy by three Abrahamic religions, who share an origin… so close and yet so far.

And when you look at the world today, clearly it looks as if it were the world of yesterday. It is full of anger and fear. And I get it. We are living with war. Oppression. Inequality. Economic uncertainty. Drought. Famine. Religious persecution. Religious extremism. Enslavement. Disease. All over the world.

Image credit: Tima Miroshnichenko, Pexels

It is part of our nature to be in conflict, which begs the question: are these conflicts simply waiting to be deepened? Or are these characteristics of a collective us to be understood, enabling untold stories to be told? Can we connect in a way to allow wisdom to be shared, to experience a future that is less about seeing others as others, and more about seeing others as ourselves?

Although we were born completely dependent on our fellow humans just to survive, I believe this lost sense of dependence — of INTERdependence – and I think that is a big part of what is holding us back from thriving as individuals, as a community and as a society.

We’ve gotten disconnected from one another, from God, from the wonder of the universe… a physical and a conceptual truth so vast our brains can hardly comprehend it. We can’t, in fact, without faith. We’ve become disconnected from us.

And that disconnection has revealed the truth about you, and the truth about me.

The truth is that we are perpetuating our conflicts, because while we often talk about seeing God up there, or in nature, or in ourselves, we refuse to see God in one another. God in us. Revealed in us.

Think with me for a moment. Have you noticed how beautiful the world is? How beautiful this country is? How beautiful your community is? When was the last time you drove around a part of your community that you don’t live or work in? I’ll be if you did, you’d see some things you’re not familiar with. And some things you are. Like people working hard. Having fun. Protecting their families. Struggling to succeed. Loving one another the best they can. See, the beauty I’m talking about is the beauty of our humanity. And it’s all around us.

Photo credit: iStock.com/adamkaz

We can choose. Connection or disconnection. Community or conflict.

If the challenge stems from seeing our identities only as differences, perhaps it is time to look at our differences in a different way.

To me, this way focuses on finding and experiencing true unity in the midst of fear, chaos and new ideas. It isn’t about finding agreement within a group of like-minded individuals, nor ignoring the root causes of our conflicts. We can’t just hug, hold hands and say, it’s all good. I mean, apologies are nice; and accountability is better. So to become (re)united, we must first be accountable to one another. We must be honest about how we’ve hurt, excluded, abused and dehumanized one another, individually and collectively.

We must use our power and privilege to right the wrongs that others experience. We must stop being willfully blinded by short-term thinking, ignoring not only what is unfair about many people’s lives, but why it is unfair in the first place.

Because by doing so, we see and honor the human in one another. We see and honor God in one another.

You and I become we. And we become us.

You know, my family represents all of these stories: Africa. Europe. The Middle East. America. Blackness. Jewishness. Christianity. Judaism. Americanness. There’s a lot of conflict there. But there’s also a lot of connection.

As I reflect on our experiences, I realize that while the urge to let these identities divide us is there, the need to connect through the differences is stronger. I realize that we must all resist the urge to be divided, because it is not our deepest truth; it is just part of our story. It’s not the whole story of us, and when we only see our division, we are prevented from seeing ourselves fully.

Contradiction and Choice: The Human Condition

As I think about these difficult choices, I think about other times we as humans have faced difficult decisions to overcome difference, to find connection in the midst of conflict, individually and collectively. One such example is found in the story of the beloved hymn, Amazing Grace.

This is a song that my mother used to sing all the time. Whenever I hear it, I am reconnected with my roots. It is also the song we sang at my sister’s funeral just a few months ago. Whenever I hear it, I feel comforted. And it is also a song that speaks to the contradictions of our human existence. Familiar to practically every denomination in American Christianity, it is sung with equal conviction in the Black church as in predominantly White churches, two parts of the Christian faith that at times look like they could not be more separated from one another.

According to “The Real Story Behind Amazing Grace,” by David Sheward, the song is performed an estimated 10 million times a year. It has been sung by Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson and Elvis – about as diverse a group of singers as one might find. I doubt there has ever been a more unifying set of spiritual verses in American culture.

And yet, this hymn was written by a man, John Newton, in England, a wayward youth whose earlier years were at sea, who worked in and profited from the slave trade for years, who himself received eight dozen lashes for trying to desert the British Navy, who was given by his slave ship captain to a West African princess, who was later rescued by another ship, which very nearly sank in a storm off the coast of Ireland.

During this ordeal, Newton experienced a spiritual conversion. And still, his transformation was gradual. He still enslaved people.

He wrote Amazing Grace in 1772, but did not renounce slavery until 1788. However, his very public renouncement – in the form of a pamphlet that was sent to every member of the British parliament, likely influenced the abolition of slavery in Britain in 1807. Which Newton was able to see, prior to his death in December that year.

If this song and its story do not reveal all of the contradictions of the human condition at once, I don’t know what does. From the enslaver, to the enslaved, to the enslaver again, to abolitionist, Newton’s story is so very human. It shows us in spite of our conflicts, in spite of our contradictions, we can still choose.

We can choose more connection and less conflict. This choice enables and reveals even more potential choices as a result:

- MORE Authenticity, courage and curiosity. LESS lies, fear and ignorance.

- MORE Faith, hope and love. LESS Doubt, despair and hatred.

- MORE working together and listening up close. LESS pretense, shouting at a distance.

- MORE trust. LESS skepticism.

- MORE respect for one another’s essential humanity. LESS demanding others conform to our standards and expectations to be human enough to deserve our respect.

- MORE seeing GOD in all of us. Less pretending God only belongs to some of us.

When we choose connection, we can navigate our conflict, through deeper, more honest conversations, like the ones we need to have within and between the Black and Jewish communities in the U.S.

We need to talk more honestly and empathetically about suffering, oppression, exclusion, liberation, inclusion and unity. We need to talk about our feelings of betrayal, and our existences within the overall structures of racism, cultural superiority and xenophobia, which seek to divide us all. We need to look inwardly about how we came to our current views of ourselves and one another, because elevating our respective cultural identities at the expense of any other does us no good, only harm.

I am encouraged by the spiritual and community leaders who are showing us this path, convening across differences to forge a strong, meaningful unity.

I think this kind of difficult conversation also needs to take place within and across a lot of communities in the U.S., not just Black and Jewish communities. Because when you zoom out and look at all of our groups in the U.S. — religious, ethnic, racial, gender, sexual orientation, generational, ideological, etc. – one commonality seems to be emerging, and that is fear: fear of losing our identities, of losing our place in society and in this world. This is scarcity thinking at its worst, and it benefits only those in power who have no desire to share their power in support of the collective progress of humankind.

You see, when we fear our own extermination, we come out swinging at one another. That is the history of conflict. Sometimes, protection is necessary, especially when extermination is threatened, or has already happened. Slavery. The Holocaust. Genocides the world over.

But as we seek our own protection, our self-preservation, what are we doing to one another? What if we cannot truly protect ourselves, without protecting one another? What if our interdependence is the key to our survival as a species, and anything else will simply hasten our destruction and our extinction? What if our inability to see God in all of us, means we do not see God in ourselves?

Speaking from firsthand experience – individually and within my various communities – I have seen that many of us who feel our identities have been assaulted and threatened, (and who in fact have been assaulted and threatened) tend to react by overprotecting those identities, to be defensive and sometimes aggressive. We go from acknowledging one another’s identities while celebrating our own, to confronting one another’s identities in defense of our own. I believe it is time that we seek solidarity through a new lens that recognizes the commonalities and connections of our trauma and pain across cultures, so that we might see each other as the same, and no longer as the other.

This is deeply vulnerable, often slow, occasionally agonizing work.

It requires deep authenticity, courage and curiosity, to be able to navigate such a chasm of difference – both real and perceived. It requires us to share our stories with one another more than we share our opinions.

It requires us to connect across our pre-existing definitions of identity – race, faith, age, parent status, and more, and it can feel like a never-ending journey. Along the way, it’s important to create new customs out of the old, new traditions that intertwine the distinctive separate parts into something new that is both instantly familiar and unrecognizable. It’s important to then memorialize those customs, to give the ancestors equal space and honor in the new, shared home, but with a focus more on the future and what is being created: a new family. This is what Darcy and I have tried to do, sometimes failing, sometimes succeeding, sometimes easily and sometimes painfully, but we continue to move forward together. And this is what we have to do as a community and a society. We need to find ways to let people feel less threatened by unity, less anonymous, and more acknowledged; giving place to their respective pasts, while focusing on what new union has been created when division is left behind. The good news is, we have always done this as a human species. We have always done this in our societies. On some levels, we already know how to do this.

The opportunity this time is to do it through connection, not conquering. To Jump the Broom AND Break the Glass. To Sojourn, America.

For more on finding unity in the face of division, read the Introduction to Sojourn, America.